To look at a Georgia O’Keeffe painting is to see America. Throughout her career, from her first show in 1916 to the late 1970s, the indomitable artist was concerned with what it meant to paint her country – and she became captivated by the wide plains, rocky outcrops and bold blue skies of New Mexico, her adopted home.

O’Keeffe’s first show was at the 291 Gallery in New York, 100 years ago this May – a fact that is being celebrated in a major retrospective of her work at Tate Modern in London from 6 July. Alfred Stieglitz, the gallerist and photographer, was shown her charcoal work by a mutual friend in 1916, and, impressed, included it in a group show without asking O’Keeffe’s permission. She wrote to ask him to take it down, he refused; a lively, flirtatious correspondence began.

By 1918, he’d tempted a sickly O’Keeffe away from a teaching job in Texas, with the offer of a flat financed by him in New York; within a month, he’d left his wife and moved in with her. There followed a creatively fertile period in both their lives, with O’Keeffe painting the city and their summer residence at Lake George in upstate New York, and Stieglitz taking hundreds of pictures of the woman who would become his wife in 1924.

But it wasn’t until their relationship wobbled, and O’Keeffe took off west, that she really found her own distinct vision of the US landscape. Recently, I visited New Mexico to explore what’s now known as ‘O’Keeffe country’ – the area around Santa Fe, home to the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and research centre.

The air crackles with static. Every shadow seems laser-cut

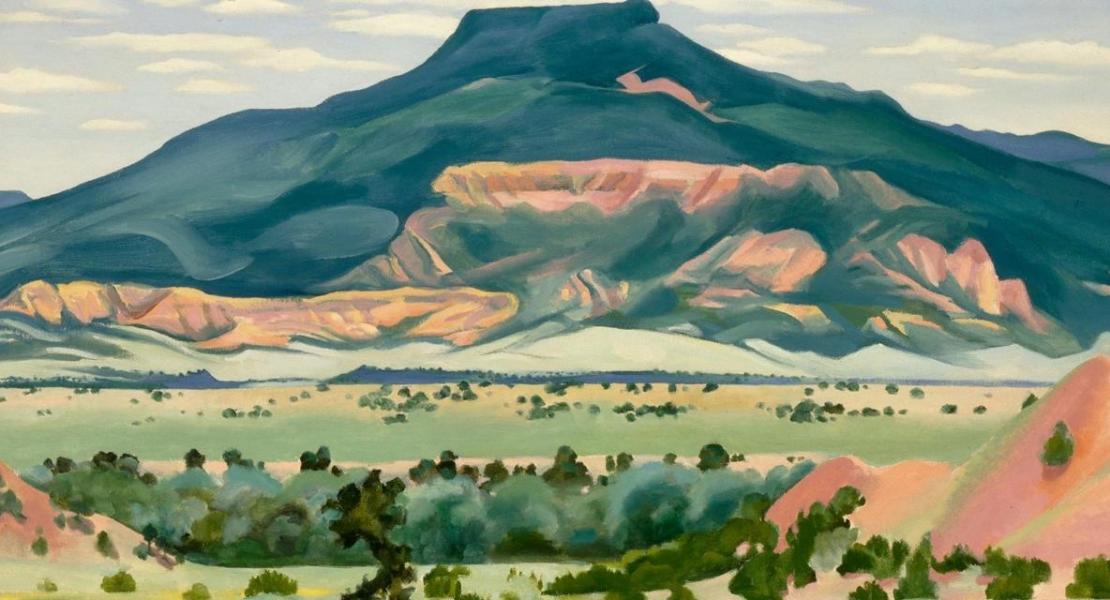

It’s easy to imagine how inspiring it must have been for the artist. The high altitude and dry climate result in a crystalline light that seems to bring out astonishing colours: the chalky ochre and smoked-chilli red of the rocks and the sun-bleached grey-gold of the prairie grasses flicker against the famous New Mexico skies, whose dark, rich blueness it would be easy to become addicted to. The air crackles with static. Every shadow seems laser-cut.

O’Keeffe first visited northern New Mexico in 1929, staying in the tiny town of Taos with friends. She needed to get away from Stieglitz, who was in the midst of an affair with the heiress Dorothy Norman. The trip proved a good idea creatively as well as emotionally: O’Keeffe was revitalised by the landscape, and fascinated by the Pueblo culture and architecture of the Native American tribes of the area.

She had found her place. O’Keeffe began to spend her summers alone in New Mexico, renting remote properties and ‘tramping’ around the countryside, taking her paints with her; in 1940 she bought an Adobe house called Ghost Ranch, and in 1945, another in the little village of Abiquiú, 48 miles north of Santa Fe. Strikingly, Stieglitz never visited: New Mexico remained hers alone.

She had also found her own form of Modernism. In the 1920s, living in New York and hanging out with Stieglitz’s masculine art crowd – Paul Strand, John Marin, Arthur Dove, Edward Steichen – she complained that the US lagged behind Europe, because American Modernists failed to engage with their own country. No wonder no-one was writing ‘the Great American Novel’ or painting the ‘Great American Vision’. “I was excited over our country [but] I knew that at that time almost any of those great minds would have been in Europe if it was possible for them,” she commented. “They didn’t even want to live in New York – how was the Great American Thing going to happen?”

Flower power

O’Keeffe grew up on a farm in Wisconsin, which is “why the landscape is important to her, becomes symbolic for her,” says Tanya Barson, curator of the Tate show. But it was when she went Southwest and discovered New Mexico, that O’Keeffe found her Great American Thing. Like her more famous close-up paintings of flowers, her vision of the Southern skies and mountains wavers between figurative and abstract; she crops in on a view, like a photographer, finding the abstract shapes and simplifying line and form, heightening colour until it has an emotive effect.

Showing many landscapes within a chronological survey of her work, the Tate aims to move on from the clichéd perception of O’Keeffe as ‘that famous female artist who painted swirling vagina flowers’. Such a Freudian reading was encouraged by Stieglitz from her earliest exhibitions, and later enthusiastically taken up by 1970s feminist critics – but O’Keeffe “consistently denied” such gendered interpretations throughout her entire career, says Barson.

Still, her close-up flowers images are beloved the world over – Jimson Weed, which features in the show, fetched the highest price ever for a work by a female artist in 2014: $44.4 million (£33.45 million). But her smooth painting style and huge popularity has seen O’Keeffe often reduced and sneered at by critics; she’s too easy.

Her smooth painting style and huge popularity has seen O’Keeffe often reduced and sneered at by critics

“Many of her works visually seem very simple; they’re approachable,” acknowledges Cody Hartley, Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Georgia O’Keeffe museum. “They also reproduce very well; they make good posters. The work appeals to a lot of people – it has an accessibility that a Jackson Pollock does not have. But actually to paint that way, so there’s not a lot of evidence of the labour involved, is very difficult. Her technique is amazing – long, continuous, smooth brushstrokes - but it’s hard to appreciate how much work and thought went into her paintings because they don’t make that obvious.”

Brits might think they know her work well, but chances are they’ve only seen reproductions: astonishingly, there are no O’Keeffe’s in public collections in the UK, and there hasn’t been a major show of her work here since 1993. This big blockbuster exhibition remedies that, bringing over 100 works to London.

A room with a view

Many of these take New Mexico as their subject. O’Keeffe moved there permanently in 1949, following Stieglitz’s death. She painted the distinctive, indigenous Adobe architecture of the region: low buildings of wide, softly curved walls made of straw and mud, that bake hard into a bright, distinctive red-brown finish. Both her homes were in this style, although she put in huge, plate-glass windows too.

O’Keeffe’s chic, minimalist house in Abiquiú is open to the public, and while visiting, I met Agapita Lopez, a local girl who became the artist’s companion and secretary from 1974 until her death in 1986. O’Keeffe was a fiercely independent woman, but in later years needed help around the house. Lopez talks shyly and respectfully of her former employer who – despite all those years together – she still calls “Miss O’Keeffe”.

“When she came [to Abiquiú], people didn’t know what to make of her, she was so odd: a single woman who always wore black,” Lopez says. “But we always had a good relationship, we got on; we were both really quiet. I came from a Hispanic family where women did not have a career, and working with her widened my horizon.”

What was it about New Mexico that O’Keeffe loved? “She loved the landscape, and she loved the light. She was still extremely independent [but] one of my jobs was to take a walk with her [so she could paint]… Miss O’Keeffe always knew what she wanted.”

From her bedroom, you can see the White Place, eight miles away: a valley sided by astonishing craggy white cliffs and spires of semi-eroded rock, brilliantly pale against the bluest sky I’ve ever seen sky. Today, it’s a popular hiking spot, but as I scramble up layers of rock for views right down the valley, I think how alien and remote it must have been in the 1940s. Intrepid woman that she was, O’Keeffe used to camp out there.

She converted a car into a mobile studio so she could work in the landscape - as well as painting from memory back in her studios. She painted several pictures of the White Place, softly flattening out the jagged fingers of rocks, white-on-blue. Her form of abstraction is about “colour and composition” suggests Caroline Kastner, curator of the O’Keeffe Museum: “she’s rejecting perspective… reducing and editing what you’re seeing in the landscape to the flat surface of a painting.”

There was one image she never grew tired of: the Pedernal mountain

15 miles north of Abiquiú, we visited O’Keeffe’s other home, Ghost Ranch. The house is not open to the public, but guided tours of the area from a nearby visitor’s centre reveal the views she painted. She painted many pictures here, with names like My Front Yard and My Back Yard, names which comically bely the grandeur of the scene. Her ‘front yard’ stretched far across ghost-grey brush and flat cracked earth, punctuated with low green juniper trees, to faraway red hills and the looming, distinctively flat-topped Pedernal mountain, smoky-blue in the distance.

Her ‘back yard’, meanwhile, looks towards striking cliffs where the different strata of rock - some dating back 200 million years – make a pastel layer-cake of colours, with improbable spires and spindly chimneys of stone jutting up towards the sky. O’Keeffe captured their varied tones, in sweeping landscapes and abstracted close-ups: elephantine mauve lumps, creamy yellow cliffs, braiding slopes of peach and pistachio, red-raw streaked rock-faces.

Her many paintings of these views seem smoothly stylised, exaggerated, too bright – but visiting, you can see how the contrasts do come from the land itself. These views also form a backdrop for her 1930s still lives of skulls and bones, sometimes floating – Surrealist-fashion – in the air; critics have suggested the morbid symbols against the desert landscape symbolise the Dust Bowl and the Depression, while for others they simply represent frontier country, O’Keeffe’s Modernist vision of the American West.

O’Keeffe painted what Barson calls “the chromatic landscape of Ghost Ranch” enough to fill a whole room of the Tate’s exhibition. Usually, she painted a subject – say, horse skulls - for around a decade, then moved on. But there was one image she never grew tired of: the Pedernal mountain. She just kept painting it, with later paintings framing the summit through the holes in sun-bleached pelvis bones.

O’Keeffe felt a profound emotional and artistic attachment to this landscape; after her death in 1986, the Pedernal was where her ashes were scattered. Not long before she died, she deemed the distant, blue-hazed summit her private mountain: “God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.”