On 27 July 1890, Vincent Van Gogh walked into a wheat field behind the chateau in the French village of Auvers-sur-Oise, a few miles north of Paris, and shot himself in the chest. For 18 months he had been suffering from mental illness, ever since he had sliced off his left ear with a razor one December night in 1888, while living in Arles in Provence.

In the aftermath of that notorious incident of self-harm, he continued to experience sporadic and debilitating attacks that left him confused or incoherent for days or weeks at a time. In between these breakdowns, though, he enjoyed spells of calmness and lucidity in which he was able to paint. Indeed, his time in Auvers, where he arrived in May 1890, after leaving a psychiatric institution just outside Saint-Remy-de-Provence, north-east of Arles, was the most productive period of his career: in 70 days, he finished 75 paintings and more than 100 drawings and sketches.

Despite this, though, he felt increasingly lonely and anxious, and became convinced that his life was a failure. Eventually, he got hold of a small revolver that belonged to the owner of his lodging house in Auvers. This was the weapon he took into the fields on that climactic Sunday afternoon in late July. However, the gun was only a pocket revolver, with limited firepower, and so when he pulled the trigger, the bullet ricocheted off a rib, and failed to pierce his heart. Van Gogh lost consciousness and collapsed. When evening fell, he came back round and looked for the pistol, in order to finish the job. Unable to find it, he staggered back to the inn, where a doctor was summoned. So was Vincent’s loyal brother Theo, who arrived the next day. For a brief while, Theo believed that Vincent would rally. But in the end, though, nothing could be done – and, that night, the artist died, aged 37. “I didn’t leave his side until it was all over,” Theo wrote to his wife, Jo. “One of his last words was: ‘this is how I wanted to go’ and it took a few moments and then it was over and he found the peace he hadn’t been able to find on earth.”

On the Verge of Insanity, a new exhibition at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, provides a meticulous and balanced account of the final year-and-a-half of the artist’s life. Although it does not offer a definitive diagnosis of Van Gogh’s illness – over the decades, a number of causes have been suggested, from epilepsy and schizophrenia to alcohol abuse, psychopathy and borderline personality disorder – it does contain a severely corroded handgun that was discovered in the fields behind the chateau in Auvers around 1960. Analysis suggests that the pistol, which was fired, had been in the ground for between 50 and 80 years. In other words, it is probably the very one that Van Gogh used.

Root cause

The exhibition also features a recently discovered letter, which has been extensively reported in the media. Written by the doctor who treated Van Gogh in Arles, Felix Rey, it contains a diagram illustrating precisely which part of his ear the artist removed. For years, biographers have debated whether Van Gogh sliced off the whole of his left ear or just its lobe. This letter, which was found by the independent researcher Bernadette Murphy, who has written about her discovery in a new book, Van Gogh’s Ear: The True Story, proves without doubt that the artist cut off his entire ear.

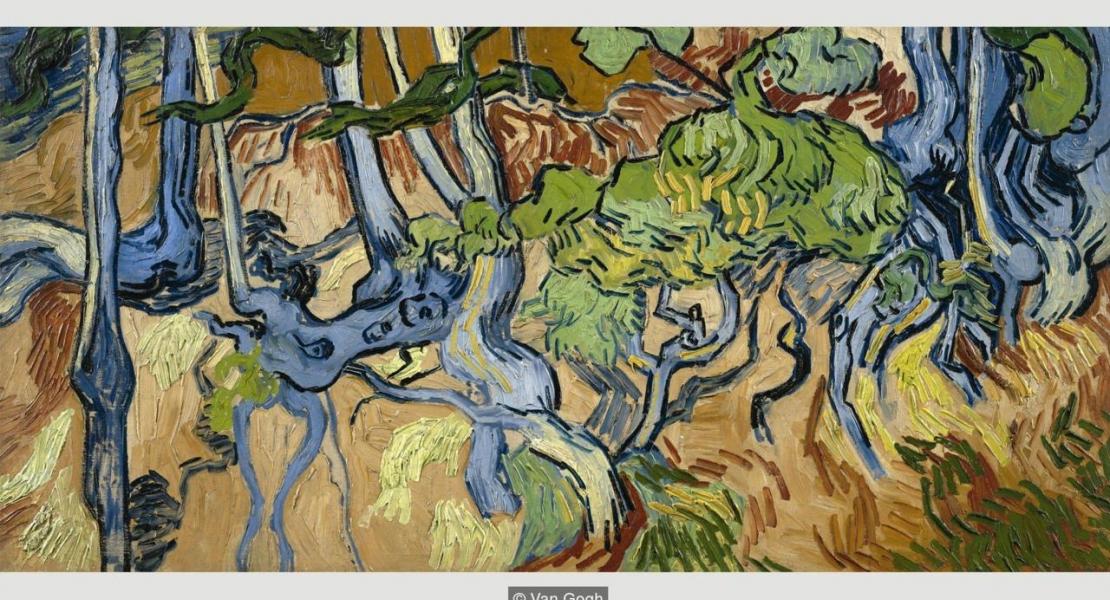

The letter, of course, is the revelation of the show at the Van Gogh Museum. When I visited recently, though, something else caught my attention: an unfinished painting, a metre across, called Tree Roots (1890). Van Gogh worked on it during the morning of 27 July, a few hours before he tried to kill himself. It is the last painting he ever made.

Tree Roots anticipates later developments of modern art, such as abstraction

At first glance, this dense picture appears almost abstract. How are we supposed to ‘read’ its thicket of blue, green and yellow brushstrokes, all vigorously applied to the canvas, which remains visible in various places? Gradually, the image resolves itself into a landscape depicting bare roots and the lower parts of trees seen against light-coloured sandy soil on a steep limestone slope. A small patch of sky is visible in the picture’s upper left-hand corner.

Aside from this, though, the entire canvas is devoted to a compact tangle of gnarled roots, trunks, branches and massed vegetation. As Martin Bailey, the art historian and author of the forthcoming book Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence, points out, “The upper parts of the trees are cut off in the unusual composition – rather as one might find in Japanese prints, which Van Gogh so admired.”

Van Gogh painted in spite of his illness, not because of it – Nienke Bakker

Indeed, in many ways, Tree Roots is an extraordinary image: an innovative, ‘all-over’ composition, without a single focal point. Arguably it anticipates later developments of modern art, such as abstraction. Yet, at the same time, it is impossible not to view the painting retrospectively – through the prism of our knowledge that, shortly after it was made, Van Gogh attempted to commit suicide. What does it tell us about his state of mind?

Goodbye to all that?

Certainly, the painting appears agitated, as though fraught with emotional turbulence. “It is one of those pictures in which you can feel Van Gogh’s sometimes tortured mental state,” says Bailey. Moreover, its subject matter seems significant. Years earlier, Van Gogh had made a study of tree roots that was meant to express, as he put it in a letter to Theo, something of life’s struggles. Shortly before his death, in another letter to Theo, Van Gogh wrote that his life was “attacked at the very root”. Could it be, then, that Van Gogh painted Tree Roots as a farewell?

When I put this to the curator Nienke Bakker, who is responsible for the collection of paintings at the Van Gogh Museum, she urges caution. “There is a lot of emotional agitation in works from the last weeks of Van Gogh’s life, such as Wheatfield with Crows and Wheatfield under Thunderclouds,” she says. “It’s clear he was trying to express his own emotional state of mind. Yet Tree Roots is also very vigorous and full of life. It’s very adventurous. It’s hard to believe that somebody who painted this in the morning would take his own life at the end of the day. For me, it’s hard to say that Van Gogh painted it intentionally as a farewell – that would be too rational.”

Ultimately, Bakker is keen to scotch the idea that Van Gogh’s illness was the cause of his greatness as an artist. “All of these tortured, gnarled roots make Tree Roots a very hectic, emotional painting,” she says. “But it’s not a painting created by a crazy mind. He knew very well what he was doing. Until the end, Van Gogh painted in spite of his illness, not because of it. It’s important to remember that.”