Stewart McPherson is prepared to go a long way for his science: even into the grounds of a prison in the Philippines. "I had to be guided by murderers," he says. His target was, appropriately enough, a plant that kills: a tropical pitcher plant called Nepenthes deaniana that traps and digests insects. "It hadn't been seen for nearly 100 years."

McPherson has been fascinated with carnivorous plants since childhood. As an eight-year-old he came across his first species in a British garden centre. Immediately fascinated, he started a collection. After a couple of years, he had filled the family conservatory with hundreds of different plants.

The young naturalist found carnivorous plants extraordinary – as many others have for centuries. But despite their startling abilities, carnivorous plants are also in profound danger.

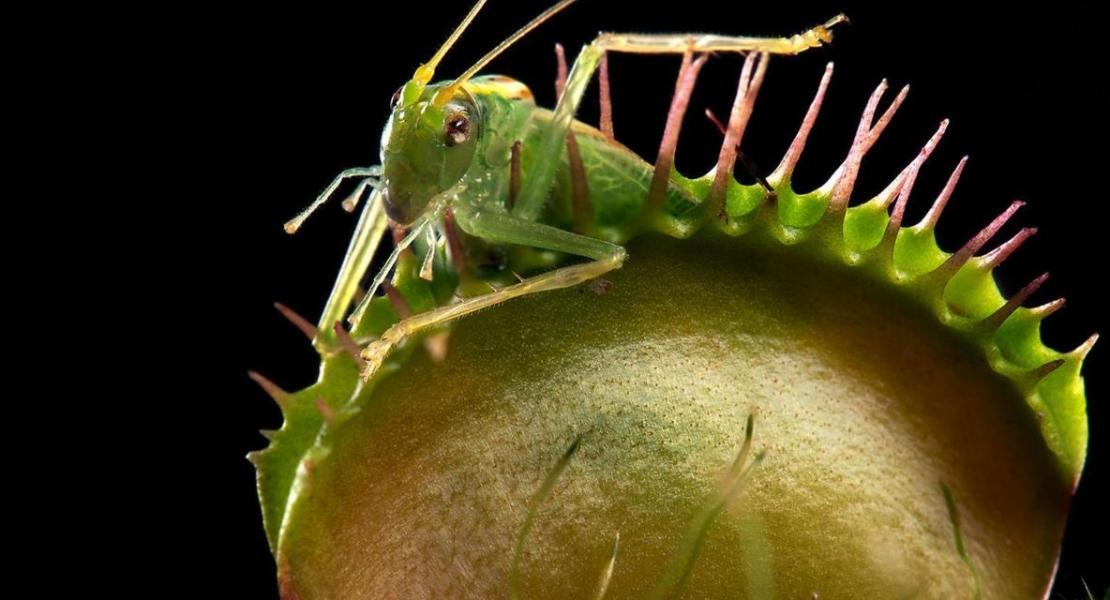

"To think they are plants with highly modified specialist leaves that have adapted through evolution to attract, capture, kill and digest animals – in some cases as big as rats – is pretty amazing," says McPherson.

Over the last decade, he has climbed 300 mountains

The idea of flesh-eating plants has long captured the imagination, from Victorian fables of man-eating species to post-apocalyptic sci-fi with John Wyndham's The Day of the Triffids and the musical fantasy film Little Shop of Horrors.

These plants were mythical, of course. The thought of real-world carnivorous plant species once seemed impossibly implausible.

So much so that when the great biologist Charles Darwin wrote about them in his 1875 book Insectivorous Plants, he was mocked for suggesting some plants were carnivorous.

"But of course he was right – as he always was – and he provided the evidence that showed these plants capture and kill animals," says McPherson.

McPherson always longed to see carnivorous plants in the wild so, after leaving university, he set out to various countries across the world to document them in a series of field guide books. Over the last decade, he has climbed 300 mountains, formally described 35 new carnivorous plants and rediscovered long-lost ones – like the Nepenthes deaniana in that Philippine jail.

Because, strange as it might seem, botanists and scientists often overlook carnivorous plants.

We had to eat frogs on the way back

"They haven't received as much attention as they deserve," says McPherson. "There are hundreds of them all over the globe that are underappreciated."

But, thanks to his and other researchers' efforts, that is changing. "In the last 10 years, more of these plants have been found than in any time in history."

Many species are found in remote, inaccessible areas of – for example – Malaysia, Indonesia and Western Australia. Some of these plants had been hard to assess because the environments they occupy are unstable and difficult to travel in.

This means McPherson has had to go to great lengths to explore carnivorous plant biology. On one "epic" trip to a remote mountain in Kalimantan in Southern Borneo, on the trail of Nepenthes pilosa, a species that had not been since 1899, McPherson and his team ran out of food.

"We had to eat frogs on the way back," he says. "We'd go out each night with a torch and look out for their glowing eyes, and catch them for breakfast, lunch and dinner."

While compiling his book on pitcher plants, he travelled to Palawan, a little-known narrow island in the Philippines. As a result of political instability in the 1980s and 1990s, few botanists had travelled to Palawan and explored the spine of mountains that runs along its length.

It's lived there for tens of thousands of years, quite possibly millions of years, and no one has known or appreciated it

It was a rich treasure trove for McPherson. "I went up all of the tallest mountains and found an undescribed species on almost every one – seven in total," he says.

The most exciting of the new species was a giant pitcher plant on Mount Victoria that he named after David Attenborough (Nepenthes attenboroughii), because of the broadcaster's inspiring passion for the natural world. The plant is big enough to put your hand inside.

McPherson heard a story from a group of missionaries who returned after a fateful trip and said they had seen "giant cup plants". He became convinced they were talking about a new species of Nepenthes. "It was immediately clear that it was a brand-spanking-new species, because it was so gigantic."

"We felt absolute elation. It's wonderful contributing anything to science or knowledge. It's lived there for tens of thousands of years, quite possibly millions of years, and no one has known or appreciated it. It's humbling to know that a plant or animal has existed in habitats for years in silence, just slowly ticking along waiting to be noticed and appreciated."

His team also found a newly-killed shrew in the plant. It had fallen in and drowned in the accumulated rainwater. Two weeks later when they returned, the shrew was a husk, digested by the plant's enzymes.

Many of them harbour little worlds of unique life within their pitchers

This kind of behaviour leads to the popular misconception that these plants are "rat-eating". It is actually more coincidental than that.

"It's not fair to say they deliberately kill [mammals], they do it through coincidence. Under very rare circumstances the same process by which they capture and kill insects, also works on [small mammals]," explains McPherson.

We still do not know very much about how these plants engage with other animals. Many of them harbour little worlds of unique life within their pitchers: animals that live inside the traps and break down the prey that the plants capture.

And some carnivorous plants have close relationships with mammals and birds.

For example, Nepenthes lowii gets much of its nutrition from tree shrews, just in a roundabout way. "The pitchers of N. lowii look like a toilet bowl. They trap the waste from birds and shrews that use it as a toilet," says McPherson.

A 2015 study suggested that a carnivorous pitcher plant in Borneo attracts bats with an ultrasound reflector, and provides a roost in exchange for their waste. The complex relationship between sundews, spiders and toads has recently been studied by scientists at the University of Maryland.

The parrot plant (Sarracenia psittacina) can capture tadpoles underwater with its lobster pot trap

There is a simple reason why carnivorous plants have such complicated relationships with animals. They usually live in nutrient-poor soil, so they have adapted to capture and digest animal prey to gain the nitrogen and other nutrients they need to survive and grow.

The beautifully ornate sundew (Drosera), for example, captures its prey with sticky, glue-like tentacles. Once an insect is stuck, the plant will fold down, trap and kill its victim. These bright reddish-crimson sundews are even found growing wild in the UK, in the bogs across the country.

Pitcher plants use pitfall traps instead of sticky tentacles. Often pitchers are vividly coloured in red and yellow, with intricate patterns. This elaborate display attracts insects, which slip down the waxy linings into the fluid below and drown.

The pitcher plant Nepenthes bicalcarata looks particularly sinister. It has two "fangs" projecting beneath its lid. There are many theories as to how these thorns profit the plant. Charles Clarke at the University of New England in Armidale, Australia, suggests they may attract insects – there is nectar in the tips.

Carnivorous plants can even capture prey underwater. The aquatic waterwheel plant uses a snap trap, similar to the Venus flytrap. It snaps shut on mosquito larvae and small crustaceans called copepods which are digested by enzymes released by the plant. The parrot plant (Sarracenia psittacina) can capture tadpoles underwater with its lobster pot trap.

Unfortunately, the beauty and strange prey-catching adaptations these plants have evolved make them attractive to poachers. Many of them are already critically endangered, which means McPherson and other botanists are racing against time to describe species before they disappear. Many are endangered and some are already extinct.

People in Europe and North America want specifically different ones, which drives people to go up the mountains, rip them out and bring them back

Although it is a common sight in garden centres, the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula), perhaps the most iconic of carnivorous plants, risks extinction in the wild. The plant occurs only in a small range around Wilmington, North Carolina. Illegal poaching is a factor in long-term population decline.

The rarest carnivorous plants can command the highest value – sometimes thousands of dollars per plant – and many of these species live in economically-deprived regions.

"Everyone has mobile phones and the internet for eBay, so there's a massive trade in the world of rare plants, and it gets bigger and bigger every year," says McPherson. "People in Europe and North America want specifically different ones, which drives people to go up the mountains, rip them out and bring them back to sell locally and internationally."

Alongside poaching, shrinking habitats due to logging, mining, agriculture, new roads and other developments is taking its toll. Because many of the plants live in narrow altitudes and ranges, they can become extinct quickly if habitats change.

Climate change could also be an issue in the future because many carnivorous plants have such narrow ranges.

To combat the decline and conserve some of the rarest plants, McPherson set up Ark Of Life in 2010. "Many species of Nepenthes are increasingly at risk of becoming extinct and in some cases little is being done."

If we don't maintain a permanent collection for them, that's it for this species, they're gone

Nepenthes rigidifolia, for example, may be the closest plant to extinction. "It's pretty much wiped out in the wild," says McPherson. "The only known wild population currently consists of one plant."

Similarly, there may only be a couple of thousand Nepenthes rajah left in the wild. This huge pitcher plant is endemic to Malaysian Borneo, and has occasionally trapped lizards, birds and frogs. The species is well protected in Malaysia's Kinabalu National Park. Even so, a landslide last year completely destroyed one of four populations, bringing it a step closer to the brink.

The challenge in conserving Nepenthes and certain other carnivorous plants is that the plants are single-sex, meaning an individual plant only has male sexual organs or female sexual organs, not both. That means you need multiple specimens of each sex to have a viable population.

A botanic garden in Holland looks after the Ark of Life collection of around 50 male and female plants. "It's small but they're really important for plants that are extinct or nearly extinct in the wild – they're the rarest of the rare," says McPherson.

The only known wild population currently consists of one plant

"Nepenthes clipeata and N. rigidifolia are the most important," he says. "Both appear to be in serious trouble and if we don't maintain a permanent collection for them, that's it for this species, they're gone. In 50 years all the people who currently cultivate them will have died."

To build up a permanent conservation collection of strains of each plant, McPherson looks for cuttings from people who already have them in horticulture. It is perfectly fine to have legal carnivorous plants at home and there are many legitimate breeders.

The IUCN launched a fundraising campaign at the end of 2015 to help complete the assessment of carnivorous plants, estimating that only 20% of species have so far been formally documented. A report in 2014 said that the primary objective was the assessment of Nepenthes species, in line with the focus of McPherson's Ark of Life.

There are other promising developments, too. The law was recently strengthened in North Carolina to make poaching wild Venus flytraps a felony rather than a misdemeanour.

Our pollution might be turning these unique plants vegetarian

McPherson has just returned from an expedition to see how the rare Nepenthes clipeata is faring in Indonesian Borneo. This species is the most imperilled of all carnivorous plants. The only mountain on which it occurs has suffered rampant poaching, and has been extensively burnt during recent years, pushing N. clipeata to the brink.

Despite extensively searching for several days, McPherson found only four adult clumps and just three small juvenile ones.

The situation is just as bleak for Nepenthes kelam, another carnivorous plant native to Indonesian Borneo. It occurs only near the summit of Mount Kelam on the island. McPherson's investigations on the mountain suggest it is close to extinction in the wild.

Human behaviour has a significant impact on carnivorous plants and it remains to be seen how the most endangered species will survive and adapt in the world.

Despite extensively searching for several days, McPherson found only four adult clumps and just three small juvenile ones

In 2012, scientists found that sundew plants in Swedish bogs were cutting back on their fly-catching because they could find nitrogen in the more polluted areas. The plants are so finely tuned to their environments that any changes can affect the way they prey and eat.

Our pollution might be turning these unique plants vegetarian.

So what is the future for carnivorous plants? Some species that occur in non-vulnerable places will be fine. But for those that are restricted to small, isolated locations, the situation is critical. A poacher could wipe out an entire population in a single trip. "It's a battle that in some cases we're quickly losing," says McPherson.