“Your father had an accident there; he was put in a pie by Mrs McGregor.”

Old Mrs Rabbit’s frightful warning to her children Flopsy, Mopsy, Cotton-tail and Peter appears on the opening page of Beatrix Potter’s first book, The Tale of Peter Rabbit. Aside from featuring perhaps the most dramatic use of a semicolon in children’s literature, it sets the tone for her work from the start: that horrors abound in a world of Darwinian struggle, but that these must be faced calmly. Your parents, and perhaps your children, may be devoured by a vengeful property owner, or sold for tobacco; you may have your tail ripped off by an angry owl; an invading rat might tie you up in string and include you as the key ingredient in a pudding. But life goes on – disappointments must be faced and tragedies overcome.

Potter’s tales have been consistently popular with adults, as well as children, since The Tale of Peter Rabbit was published in 1902 when she was 36 years old. This is not just because they feature adorable creatures in harrowing situations; her talking-animal stories also comment on the era’s class politics, gender roles, economics and domestic life. Did she examine British society through animals because she spent more time with animals than children, aside from her brother Bertram, when she was young? Because she wanted to rebel against the bourgeois values and morals of her wealthy middle class family – which had made its money in the textile industry – but only dared do so through furry surrogates? Because she could only publish children’s stories since her true passion, science, was a career field closed to women in the late 19th Century? Because she had a German tutor who introduced her to the back-to-nature ethos of the Romantics?

The one thing we do know for a certainty is that when Potter depicts mice wearing aprons or rabbits smoking pipes, her stories inevitably reveal as much about human virtues and follies as they do the natural world. As M Daphne Kutzer writes in Beatrix Potter: Writing in Code, “She never attempted to write a novel, but it is fair to say that a number of her small children’s books are in fact novels: their characters and their plots are as complex and open to interpretation as any novel published at that time.”

Of mice and manners

Commentary on British social relations of the early 20th Century appears everywhere in Potter’s work. Her writing style has a tone of observational detachment, as if she were a journalist profiling these animals. (In The Tale of Ginger and Pickles she writes of the cat Ginger, following his financial bankruptcy, “I do not know what occupation he pursues,” as if she were reporting this story rather than making it up.) She rarely focuses on the very rich, nor the very poor; her characters work for a living. Like Kenneth Grahame’s anthropomorphic animals in The Wind in the Willows, published six years after Peter Rabbit, Potter’s characters have been shaped by the transfer of power in British life from the landed aristocracy to the bourgeoisie, the class from which Potter herself had sprung. “Nearly all of [the stories] are preoccupied with hierarchy and power,” writes Kutzer – and they reflect and embody middle-class values. Industriousness is a cardinal virtue in Potter’s characters – whether it’s the lovable tailor of Gloucester, the domestic goddess Thomasina Tittlemouse, or the squirrels who diligently gather nuts on Owl Island and whose ingenuity the author clearly admires.

Indolence is the greatest sin, whether from the upper class or the lower. Samuel Whiskers wears the jacket and waistcoat of a landed gentleman but mostly sits around all day snorting snuff, while his wife waits on him. Squirrel Nutkin lets his more mature peers collect nuts while he plays “ninepins with a crab-apple and green fir cones”. The Flopsy Bunnies are stolen by Mr McGregor because of their gluttony: they fall asleep after eating too much.

Potter regards stupidity with similar contempt. In the celebration of laissez faire capitalism that is The Tale of Ginger and Pickles, she approves of the market forces that ruin the title characters’ shop, because they didn’t run their business with intelligence – they decided to grant unlimited credit to all their customers. She also disapproves of those who would take advantage of the stupidity of others, such as Mr John Dormouse, who sells defective candles to his neighbors: “And when Mr John Dormouse was complained to, he stayed in bed, and would say nothing but ‘very snug;’ which is not the way to carry on a retail business.” However, she approves of the savvy businesswoman Tabitha Twitchit, who raises her prices when her competition is eliminated by Ginger and Pickles going bust. Twitchit has three kittens to raise, yes, but it’s also just good business. Potter’s vision is that nature may be Darwinian chaos but one can survive through hard work and good sense.

Rebel with a cause

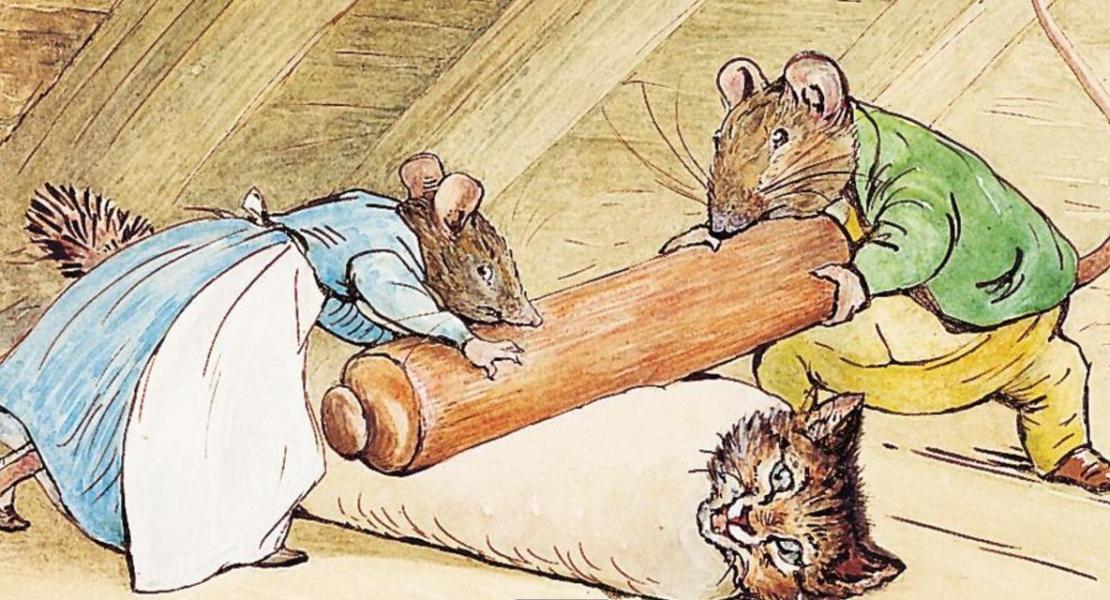

For Potter, the gradual shift from landed wealth to trade and industry is inevitable and sensible. But she opposes violence against individuals, even if she depicts it. However, she can revel in violence against symbols of widely accepted social conventions. Critic Humphrey Carpenter writes in his essay Excessively Impertinent Bunnies that she displays a “most vigorous contempt for the most accepted of Victorian social values” and is “definitely on the side of the transgressor”. Potter is positively gleeful in her description of how vandal mice Tom Thumb and Hunca Munca destroy a doll-house. The doll Lucinda lives there with her cook, Jane. For most of the story, Potter depicts the dolls as having nothing to do but sit around, pose and look pretty in their tiny red-brick abode. They’re not only indolent, they lack common sense: after the dolls leave the house the mice find “the door was not fast”.

The proletarian mice try to eat the food the dolls left behind, but the ham and fish are actually made of plaster: they are an ornamental frippery of the rich. So the mice proceed to destroy the meal with fire tongs – it’s flavourless, lacking in nutrition, rigid and easily shattered – then rip up much of the rest of the dollhouse. The destruction of an artificial replica of a Victorian household suggests that, for Potter, Victorian domestic life is just as artificial. The mice emerge as the good guys when they compensate Lucinda and Jane Doll-Cook for the damage, and Hunca Munca goes so far as to sneak into the dollhouse each morning and tidy up, without the dolls’ awareness – “the kind of hyperreal turn Umberto Eco would have appreciated,” writes Stuart Jeffries in The Guardian. Like the working class, the mice are still driven by needs while the upper class that controls their destiny is driven by wants.

Patty-pans and patriarchy

When Lucinda and Jane Doll-Cook are away, they’re out driving in a perambulator. It’s hard to see that mode of transport as anything but Potter’s commentary on the infantilisation of women by proper society at the turn of the 20th Century. Another story, The Tale of the Pie and the Patty-Pan may feature the strongest critique of women’s roles at that time. The two lead female characters conceal the truth from each other – that they both have reservations about their upcoming party. Duchess, a dog, tries to replace a pie baked by Ribby, a cat, with one of her own, since she thinks Ribby’s will be a mouse pie. It’s a complicated comedy of errors that climaxes when Duchess chokes on what she assumes is a “patty-pan” baked into her pie; she’s gagging on a symbol of female servitude. But it turns out she was actually served the mouse pie after all, with no patty-pan. Her choking is the response of a hypochondriac – an act symbolic of how something non-existent in the physical world, such as man-made social conventions, can still constrain to the point of gagging and hysteria. And how proper society forces women to lie to each other, and to themselves, to avoid giving offense.

How much of this commentary on class, politics, business and etiquette came directly from Potter’s own experience? Biographical accounts of her life suggest a great deal. Her home life with her parents was a heightened version of the stereotypical Victorian household: her father spent his days at the club, her mother was expected to do nothing and both of them objected to Beatrix’s engagement – at age 39 – to her publisher Norman Warne because he was ‘in a trade’, even though they had made their money in the same way. After Warne died before their wedding, they objected again when she finally did marry William Heelis at the age of 47 – it was unbecoming, because her husband was a lawyer. In Beatrix Potter it seems the personal and the political, the private and the public are perfectly joined. Perhaps that’s why her animals don’t just talk, they have something to say.